An Afternoon

Srijoni Banerjee

Bimal realized that his past ailment had started bothering him again. A collector had come knocking at his door after several months, her face half-covered in a mask. The pandemic had begun to recede slowly. Bimal greeted her and offered a few drops of hand sanitizer. That was then followed by other rituals to make her feel welcome. Previously, guests would be first greeted with a glass of water, followed by tea and some sweets, but the pandemic changed everything. Isabel, from Spain, in her sixties, sat stiffly, sifting through Bimal’s paintings.

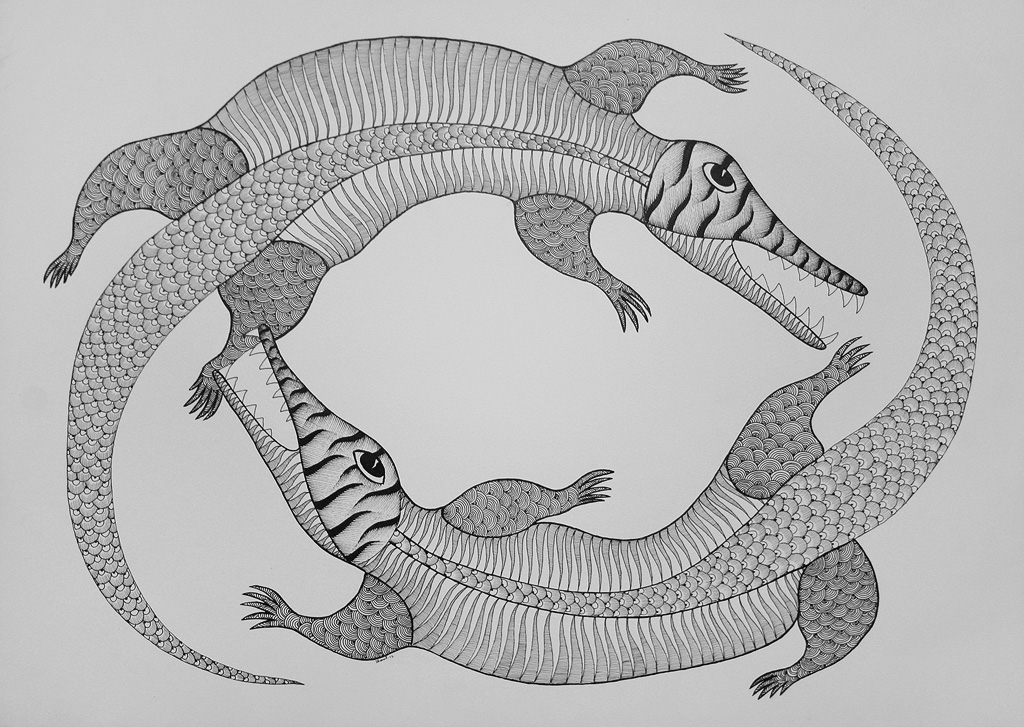

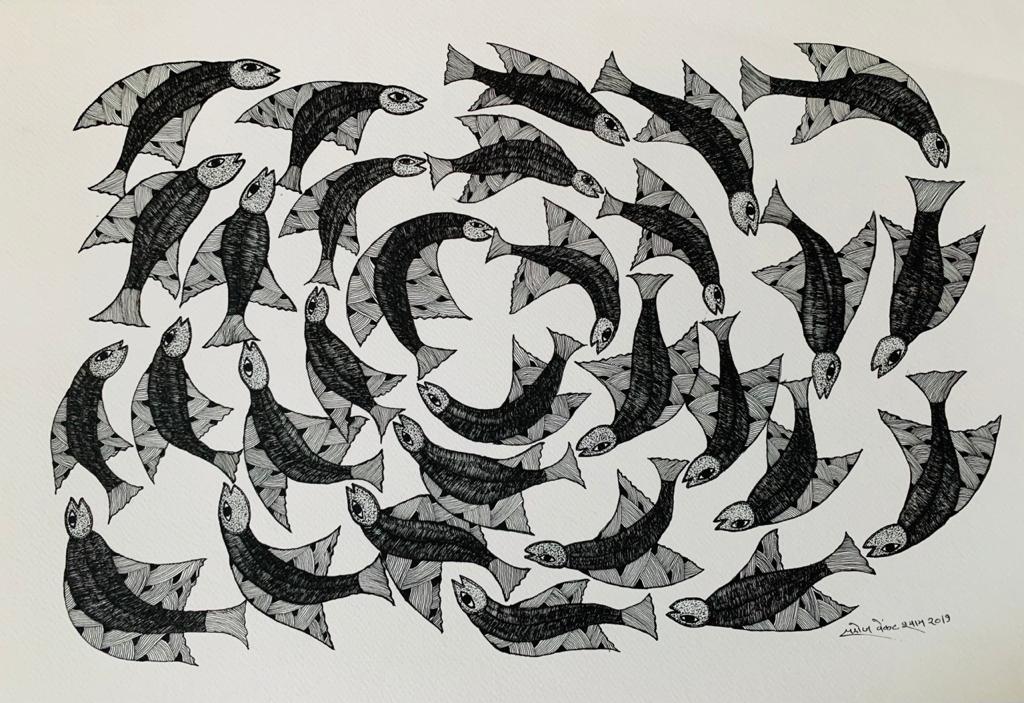

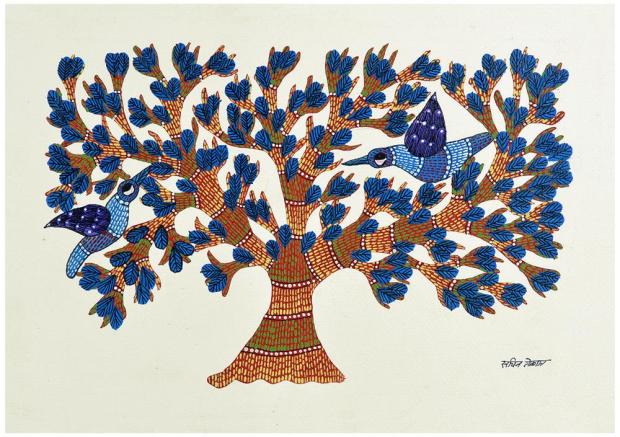

His paintings have always been a blend of very bright colours, a bit unusual because the way he uses his palette is quite different from other artists. This is not his own opinion. Eminent critics have said so in several reviews. His canvas has always been a ferment of bright hues. There came a time, however, when he started losing colour. Almost twelve years ago, after his transfer to the steel foundry, colours started to fade. One’s job always affects one’s lifestyle and even one’s mind. His job was always at odds with his creative side. He was at the same time an artist and a worker in a locomotive factory. However, the new surroundings in the foundry were completely incompatible with his temperament.

Continue reading