A Death in the Forest

Paromita Goswami

“Hey there!” shouted one of the seven policemen who had just walked into the dusty Adivasi village. Katiya happened to be returning from his sister’s house and guessed that he was being yelled at. He looked down and tried to saunter on as if he had not heard them. “Hey you, are you deaf?!” This time the shouts sounded more like threats. A woman, who had just stepped out sickle in hand, quickly turned round and disappeared into her hut. Children with mud-streaked faces peeped out from behind trees. Katiya stopped as the men strode towards him.

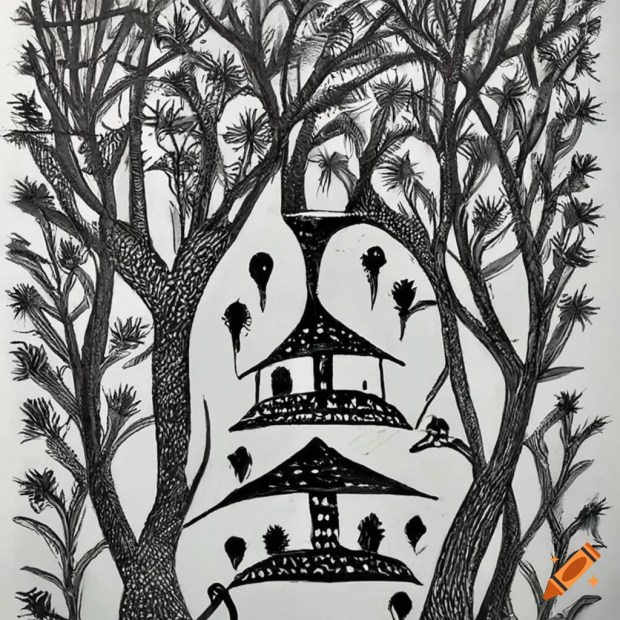

“Ah, just the person we wanted to see,” said the Inspector, playing friendly but placing a firm hand on his shoulder, “let’s go to your house and sit for a while.” Most unwillingly, Katiya led the group to his hut right at the end of the village. The dense, hilly Koparshi forest seemed to come right up to his little backyard. The village dogs ran around yapping; the hens stopped pecking at worms in the soil and flapping their wings vigorously, hid the chicks swiftly underneath.

The policemen settled on the string cots in Katiya’s outer courtyard; the red plastic chair was reserved for the Inspector. Katiya fetched water for them to drink and splash on their faces. Then he slaughtered four chickens and his wife made red hot chicken curry and rice. Katiya watched from a distance as the police chewed and sucked, licking their fingers clean, making noises of satisfaction at the curry’s spiciness and tang. Their rifles stood delicately balanced against their knees.

“Look, Katiya, we know you are a good man,” began the Inspector, gargling and spitting at the side of the wall, “but news has reached us about you…very disturbing news.” He wiped his thin moustache delicately with a white handkerchief. “Katiya, I call a spade a spade. You may call them Dadas but I call them Naxalwadis. And I have learned that a group of Naxalwadis paid you a visit some time back. I am surprised that a good man like you is helping them.”

“Naay, Sahib. Amhi gareeb manse ahot – we are poor people,” pleaded Katiya.

“And yet you did not inform us.” The Inspector peered into Katiya’s face, his face grimacing as his tongue dug deep into his teeth for stuck chicken. “Next time you hide your Dadas and feed them, you will find yourself in custody. Got it?” he said, spitting out husks of food.

“Yes Sahib.”

“Now listen carefully and look up when I talk to you!” continued the Inspector, “We know that the Naxalwadis are in this area. If you know anything about their movements, now is the time to tell me.”

That night Katiya twisted and turned in his bed. It was true that the Dadas had walked in for a midnight dinner three days back, but they had left immediately afterwards. How did the news reach the police? He knew that henceforth he would be under surveillance. And now that the police had eaten his chicken, the Dadas would haul him in for questioning. Katiya felt trapped. He felt the familiar urge to run away into the forest. The cool green forest was his respite from the relentless negotiation with the outside world – the police, contractors, foresters, the Dadas. Fifty year old Katiya had struggled his entire life to master the tricks of not getting fleeced or beaten, of finding work and getting paid a couple of bucks but never had he felt as weary as tonight. The smiling face of the Inspector floated into his dreams and he woke up in panic.

When dawn came, he went over to his sister’s house and called out to his nephews Chinna and Mainu. “Let’s go fishing,” he suggested in a tone of false joviality. He was fond of the sturdy lads who eagerly accompanied him wherever he went. This morning however they tried to wriggle out of it – they had heard of the policemen’s lunch and did not want to be seen anywhere near Katiya. Jabbebai, their mother, scolded them roundly for laziness and disobedience and pushed them out of bed while she packed a kosari rice snack, thick rotis with green chillies, salt and onions. Katiya grinned as he stacked a couple of aluminum pots, a knife, a towel, a torch and a matchbox in a cloth bag. Eventually, Chinna picked up an axe and Mainu hauled the two bags over his shoulder.

The trio entered the thick forest walking in a single filed under shady canopies. Along the way Katiya peeled the bark of the bartondi tree with his sharp iron knife, enough to fill a small polythene bag. His mood had lightened and he had already forgotten the previous day’s incident. This verdant forest was his safe world – he knew it like he knew and trusted his parents, siblings, and friends. He could pluck a flower to stick behind his ear, suck on bits of honeycomb still dripping with golden honey, and roast a rabbit with his friends.

Making their way through the foliage, they stopped at a place for lunch and a nap before proceeding deeper into the forest.

“I didn’t want to come today,” pouted Chinna stretching out on the grassy forest floor, “there is no fish in the stream these days.”

“Oh really boy, who told you that?!” said Katiya, “Wait till I show you this spot – the fish is just waiting for you!”

By evening they reached the Pamul stream. They washed themselves in the dappled, sparkling water before beginning the tedious work of extracting bark juice. Katiya set the heap of bartondi bark on a large, flat, black stone, poured some water to soften the mass and Chinna walked around to find the right-sized stone to use as pestle. The brothers took turns to pound the bark till thick purple juice flowed from it.

“Hey Uncle,” huffed Chinna, wiping his sweaty face on his forearm, “this colour doesn’t look right to me. Shouldn’t it be brown? Are you sure you got the right tree?”

“You carry on, boy; the fish won’t mind a little change.”

Mainu sat humming nearby. He spoke little but hummed a lot. Like Katiya he too liked tucking fat, red flowers above his ears. Katiya dropped the juice and the pounded mass into the stream where it formed a deep puddle and the water turned a dark crimson.

Tired, the three men set themselves around a crackling fire. The kosari rice in their bag was not enough for dinner so Chinna caught a couple of lizards, skinned them and threw them in the fire for a quick, tasty roast. Raw onions, salt and chillies added a nice tang and the three of them ate to their fill before falling asleep around the embers. It was nearly afternoon when they woke up the next day. Mainu was the first to run to the stream. Yes! There were fish, lots of fish floating on the top.

“Dumb fucking fish,” snorted Chinna, gleefully and the brothers laughed together.

The three waded into the stream and stayed in the serene waters for a long time. Katiya set his thin cotton towel to carefully gather the catch. It was as if the other world did not exist at all – the terror-ridden world of policemen and Dadas. He poured the catch into the aluminum pots, covered the mouths with pieces of white cloth, tied in place with strings. The pots went back into the cloth bag, one on top of the other.

They set out homewards laughing and planning a village feast. They thought they had walked long enough and yet their village remained out of sight. At first, the boys chided their uncle for playing a trick on them, but the puzzled looked on his face disconcerted them. Their humming and the banter soon disappeared. They walked on in silence, rested to quench their thirst, plucked some berries, chewed some leaves and then walked again. The forest paths grew longer beneath their feet and the pots in the bag grew heavier. They plodded on in fear and dismay as the forest expanded endlessly before their sight. The familiar trails that should have veered homewards narrowed and disappeared mysteriously between huge, crooked tree trunks. Bewildered, Katiya narrowed his eyes and retraced his steps again and again. The ancient trees that had forever been his friends now seemed to gather around silently like giants with arms spread out, blocking the way. Gnarled roots emerged from the earth like twisted, slimy snakes making them stumble. Impenetrable bushes appeared out of nowhere, thorns grazed their bare arms, legs, and faces till thin lines of blood appeared on their bodies.

The three trudged on blindly, weeping in the semi-darkness of the forest, groping at each other for support, grunting like beasts, calling out to the gods for help. All of a sudden they found themselves on the edge of an open grassy patch. They rushed ahead in relief. Tired to the bones, they slumped under the solitary tree that stood in the middle of the clearing. Chinna was burning with fever. Katiya swallowed some water from a plastic bottle before pouring the last few drops into Chinna’s quivering lips.

“We should keep moving,” whimpered Mainu.

“But Chinna is not well,” replied Katiya hoarsely.

“I am not going to stay here, I want to go home,” sobbed the lad.

Katiya squinted in the dimming twilight. He walked around a few steps and saw the outline of a tarred road at a distance. Which road was this? Where did it come from? Where did it lead to? In a flash, he regained his bearings and broke out in a cold sweat.

“This is the road that goes to Kermili village. We have wandered far from home, too far. We are on the other side of Koparshi forest,” he gasped. “The Dadas must be in Kermili, or somewhere nearby. I heard talk in the market that there is a meeting in Kermili today … or was it yesterday?” His wide eyes looked around fearfully.

“And the police … are they around too?” Chinna strained to get the words out of his parched throat. Katiya nodded without answering.

Darkness began a slow descent around them. In the forest, darkness falls like a black cloud, swiftly, profoundly, enveloping everything in its embrace. In the sudden dark, the chatter of monkeys, the chirping of crickets, the rustling leaves, everything sounded menacing. Katiya did not dare to light a fire. He sat on his haunches facing the road while the two exhausted brothers leaned against the tree. A dog’s sudden bark pierced the air. It was not the thin yelp of a village mongrel, but an ominous howl. Katiya rushed swiftly towards the road, peered into the dark and came back running.

“It’s them, it’s them,” he hissed, gesturing wildly towards the road.

Mainu opened his mouth but Katiya clapped his palm over it. He gestured to Mainu to pick up the cloth bags and leave the axe behind. Then slowly he slipped an arm under Chinna’s shoulders. Chinna’s eyes remained closed and he mumbled deliriously.

“Come on, boy, come on!” urged Katiya in a voice hardly audible, “Stand up, boy, lean on me! Lean on me!”

With great difficulty, Katiya stood up with Chinna’s fevered body leaning against his, but before they could take a step, there was great commotion on the side of the road. Katiya’s heart leapt violently. His eyes grew large with brute fear as he saw silhouettes of armed men and ferocious dogs straining on their leashes. Menacing gunclicks were followed by blood-curdling screams as men fell flat on their stomachs.

Katiya felt the gorge rise to his throat. Chinna’s head lolled on his shoulder. Mainu wailed like an animal before the butcher’s knife. The next moment Katiya kneeled down and with difficulty he propped Chinna under the tree, spreading out his legs before him. Then he stood upright again and put his hands up in the air, “Adivasi!” he tried to shout in the direction of the road, “Adivasi, we are Adivasi!” His voice came out as a pitiful strangulated croak.

The first shot rang out. Terrified, Mainu dropped the bags from his shoulders and the clatter of the fishpots echoed in the darkness. More bangs followed. Katiya had lived in the Red Corridor long enough to know that this was the worst nightmare, one from which there was no waking up. Mad with fear, he bent over his sick nephew and cried, “Chinna don’t move, don’t be afraid. Just don’t move!” Chinna did not reply.

Then Katiya grabbed Mainu’s wrist and pointed to the forest behind them. Mainu winced, “No, no, please no!” But Katiya gripped him harder.

“Mainu! Mainu! Listen to me! It is better in the forest! They will kill us here.”

Another shot whizzed across the clearing and hit the tree trunk. Katiya and Mainu ran into the forest shrieking. The forest was in pitch darkness and yet Katiya ran through it holding Mainu’s hand – he knew every tree, every leaf and every twig that snapped under his unshod feet. At first, they heard the heavy boots behind them and the snarling of dogs, but with each step closer home all they heard was their own hearts pounding. It was close to daybreak when they crept home in shambles, their minds and bodies frayed with terror and guilt.

But what happened to Chinna who was left under the tree? He died in the shootout. The patrolling party tied his body to a bamboo pole and policemen took turns to carry it to the police chowki where he was kept overnight. Next day, a police van took the body to the government hospital for post mortem and the same van brought Chinna home to his village. The police constable who accompanied the body took aside a couple of elders and advised them not to remove the shroud in front of his mother – “eight bullet injuries…she may not be able to take it.” The white shroud provided by the hospital was bloodstained. Mainu howled, tore at his hair and clothes in pain and remorse, beating his chest in frenzy.

The entire village huddled in grief outside Katiya’s house.

“What happened, Katiya? What happened? How did Chinna die?” they asked again and again.

“The police crossed us at the clearing beside the Kermili road…” replied the weeping old man.

“And?”

“And they had massive dogs with them.”

“And?”

“I shouted ‘We are Adivasis!’ But they opened fire. Chinna had a fever. He could not move so I set him under the tree and we ran into the forest…”

“Katiya,” asked the people, unable to comprehend his story, “How did you reach the Kermili road on the other side of Koparshi jungle? Why did you wander so far? Why did you not return home?”

Katiya wept wretchedly and said nothing. Who would have believed that the forest had punished them like a malevolent deity and led them to death?